SWEPT OFF MY FEET

In a novel I just finished reading, a character experiences a case of Stendhal syndrome.

I’d never heard of this. Named after a 19th century French travel writer who first described the condition, Stendhal syndrome refers to a complex of symptoms that occur when someone is psychologically and physically overwhelmed by a work of art. It presents in some ways much like a panic attack, including erratic heartbeat, shortness of breath, sometimes fainting, and hallucinations.

It’s not all bad, though. It’s also described as an ecstasy. A bliss or euphoria that sometimes requires medical attention.

Stendhal wrote of his own experience: “Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty… I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations… everything spoke so vividly to my soul.”

The condition is also known as “Florence syndrome” because it seems to happen especially to tourists in Florence, Italy. Indeed, that’s where it first hit Stendhal. Some studies have observed that it seems to afflict only tourists. Only foreigners, never native Tuscans, which is interesting. This has led some to dismiss the phenomenon as simply a byproduct of jet lag or the general disorientation caused by travel to crowded tourist sites.

But I wonder if it has something to do with our tendency to appreciate more that to which we are unaccustomed. When we are strangers in our surroundings, everything is unfamiliar. We see it all differently. Perhaps we see it better, more clearly, how extraordinary it truly is.

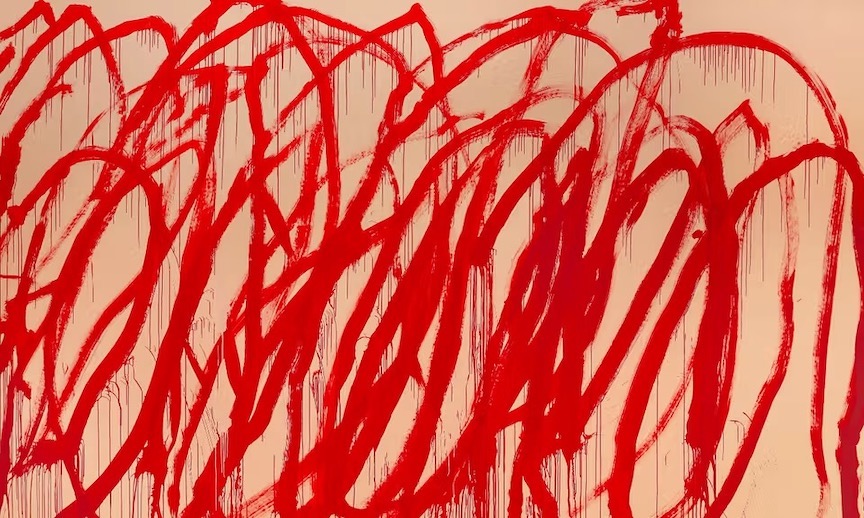

Another cool and key distinction of Stendhal syndrome is that it is a reaction specifically to the beauty of art and architecture. People might describe similar feelings of awe and overwhelm in the presence of natural wonders, and that’s all well and good, but it’s not Stendhal. Stendhal is about the magnificence of human creation, explicitly. It’s when we’re swept off our feet by something another human being has wrought.

I don’t believe I’ve ever had a full-blown case of Stendhal syndrome, but I recognize it, somehow. Certainly, it sounds feasible. I don’t think it’s just jet lag or American tourists being overly dramatic. I can imagine appreciating a work of art so deeply as to be utterly overcome by it. To lose all sense of self in it.

I’ve described before my pubescent encounters with my parents’ coffee table book of Michelangelo sculptures, and how the David was like my first boyfriend. I remember also, when I was a child visiting New York City for the fist time, an experience of rapturous vertigo when looking up at the Empire State Building and other skyscrapers. I get it.

Human creativity, human potential, is sublime. It’s freakin’ astonishing — what one person can do and make, individual pieces of art. And then what we can do together, in cooperative collaboration, exercising vision and ingenuity and skill — the mind-blowing aggregate of brilliance that comprises a culture. We are immersed in such extraordinary beauty! Why doesn’t it take my breath away all the time?

Perhaps it’s the familiarity of it. Familiarity breeding, if not contempt, then usually indifference. Maybe this is a coping mechanism. I mean, it would be hard to get much done if we were always stumbling around in orgasmic stupefaction. So we adapted by getting a little numb to glory most of the time, just to function.

I must say, though, after reading about Stendhal syndrome… I wouldn’t mind a little more of it.

What if I met everyone’s accomplishments, great and small, as if I were a stranger, encountering them for the first time? What would life be like if I let myself get carried away by the work of humankind?

I expect it would feel like falling in love. Falling in love with each other, individually, and with all of us, in general. Falling in love with our capacity to design and to appreciate, to build and to experience, to create and to live amidst our creations.

I can’t wait to be with you this Sunday, February 26, 10:00am at Maple Street Dance Space. With the divine Patty Stephens. XO, Drew

©2023 Drew Groves